Camping In Antarctica

Camping in Antarctica At 67° 51’ South, 67° 12’ West latitude, along the western coast of Graham Land, Antarctica, is

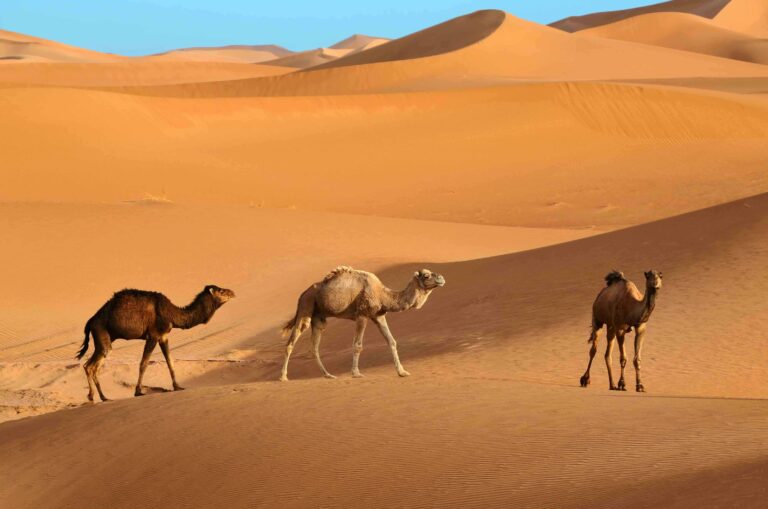

When someone mentions the Sahara Desert, images of wind-swept sand dunes rising hundreds of feet come to mind. While this is not inaccurate, the reality is that only a small part of the world’s largest desert contains these types of features. Most of the Sahara Desert is mainly hard, rocky plateaus, known as hamadas. The sand seas, or ergs as they are called, only form a small portion of the desert landscape.

While trekking through the hamada might be interesting, the real fun is venturing into these ergs riding on the back of a camel as it takes you to an oasis or small settlement. Winding around or over the sand dunes is very disorienting and one can quickly lose one’s sense of direction since everything looks nearly identical no matter what direction you look. A local guide who knows their way is not just a good idea – it can be a matter of life or death.

When our party of four arrived at the outskirts of Erg Chebbi in south-eastern Morocco, we were in luck. Stretched out before us was the sea of sand that we all imagined the Sahara would be. After a short orientation, we transferred our packs from the Land Rover over to these majestic animals that each of us would be riding for the next several hours. Preparing for the camel trek was quite an experience. Along with a local Berber guide who would lead us to our campsite, we were each given our own camel. The saddle was cushioned with thick blankets to offer us a comfortable ride over the dunes (or at least as comfortable as possible). Our overnight bags were tied down to the saddles. It is a good idea to keep these bags small. For one, you don’t need much for a night in the desert. Also, it isn’t very practical to tie a Samsonite to side of a camel.

The steps required to getting onto a camel can be quite amusing. Standing along the side of the animal, we take our inside leg and swing it over camel’s back and hoist ourselves into the saddle. Then, we hold on to the handle bar and lean as far back as possible. This is necessary because camels stand up with their hind legs first. If we don’t hold our torso back, the sudden movement can jolt us forward, causing our forehead to hit the metal handle. The camel then raises its front legs and comes to a full standing position. When sitting, the camel does the reverse motion. The front legs go down first, followed by the rear. We were also provided lessons on how to steer, advance, and stop. This could become handy if a camel decided to veer off from the pack and run off into the dunes on its own.

Once on the move, it is best not to be too tense or rigid in the saddle. Camels have a particular style of walking which causes them to sway from side to side. It is important to stay loose in the saddle and stay in sync with the swaying movement instead of fighting it. It is a much more comfortable ride that way. The Berber guide led the way on foot and the rest of us got into a single file camel caravan as we followed him into the sand sea.

Traveling by camel is one of the oldest modes of transportation anywhere on Earth. There are three surviving species of camel today. By far the most predominant is the one-humped dromedary, which makes up around 94% of all camels and is the species found across North Africa. A dromedary camel has an average lifespan between 40 to 50 years and a fully grown adult can stand to about 6’1″ (1.85 meters) at the shoulder. When running, a dromedary can sustain speeds of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h), and even get up to 40 miles per hour (65 km/h) for short bursts.

Contrary to popular belief, camels do not store water in their humps. Rather, they are reservoirs for fatty tissue. By concentrating the fat in the hump, camels minimize the insulating effect of fat, allowing them to survive in the hot desert climate. When this tissue is metabolized, it allows the camel to yield more than one gram of water for every gram of fat processed. Dromedaries have evolved to go long periods of time without consuming water and can survive for as long as 10 days without drinking. During this time, a Dromedary can lose as much as 30% of its body mass due to dehydration. Once it arrives at a water source, however, a camel can drink up to 40 gallons (151 liters) of water at once.

We arrived at the Berber camp at dusk. It was a semicircular camp ground containing around a dozen large tents. We piled our gear into the one we were assigned for the night. Dinner was served soon after around a camp fire. This was followed by a music presentation under the night sky. The small cadre of Berbers livened up the camp by playing an exotic set of songs over the next hour. Guests were encouraged to participate by dancing or playing some of the instruments themselves. A few of these instruments included the darbouka, bendir drums or a flute-like instrument called a lira.

Despite the liveliness of the entertainment, what caught my eye was the night sky. It was brilliant. Walking out of the camp and over a nearby dune, it’s amazing how quiet the desert is. Staring at the night sky, I was struck by the density of the stars that were visible from one end of the horizon to the other. It is a natural dark sky preserve where the Milky Way band jumps out as you.

Early the next morning, we were wakened well before the sunrise. A small breakfast of tea and biscuits was served and water was packed for our return journey. We were leaving the camp behind before the first rays of the sun peeked over the dunes. Despite being late October, it gets hot quickly in the desert. Aside from a large hat, there are some essentials one needs to have: lots of sunscreen, a good pair of sunglass as the natural and reflected light is very bright, breathable clothing to wisk away the sweat, and twice as much water as you think you’ll need. Dehydration happens quickly in the desert, and if you are not used to it, you may come out of the experience feeling sick if you don’t keep drinking water.

Looking back at this incredible experience into Erg Chebbi on the edge of the Sahara Desert, one of the primary lessons we gained was the appreciation and challenges of this way of life. As a traveler from a western country, this was an excursion that I participated in for a single night. However, there are entire communities that live this way day-in and day-out, and have been doing so for hundreds of years. It is incredible how well humans can adapt to so many extreme environments.

Camping in Antarctica At 67° 51’ South, 67° 12’ West latitude, along the western coast of Graham Land, Antarctica, is

A Night of Sand and Stars in Morocco When someone mentions the Sahara Desert, images of wind-swept sand dunes rising

Tracking Rhino’s in a South African Game Reserve In 1935, the famed American novelist and world traveler, Ernest Hemingway published his